Small errors show the big problems with AI

Simple prompt failures can highlight the catastrophic limitations of a LLM's logic process. When the attention logic breaks, a Tesla will run over a pedestrian or crash into a concrete wall.

Education, AI, and security are intersecting issues. Just this week, a graduate student sent me a thesis proposal using a social theory that doesn’t exist (AI hallucination). We also learned AI security cameras sent another false alert for a gun at a school. An update to my university gmail account is now suggesting multi-paragraph email replies full of random and unrelated info. All three of these situations create new risks and consequences. Citing fake papers and theories can be the end of someone’s academic career and AI has made this an easy trap for students to fall in. Sending police racing to a school for a false alarm can get someone killed. An AI email reply to a student about an assignment or meeting that doesn’t exist causes confusion and distrust. All three of these problems are rooted in the same foundational flaws at the center of AI models.

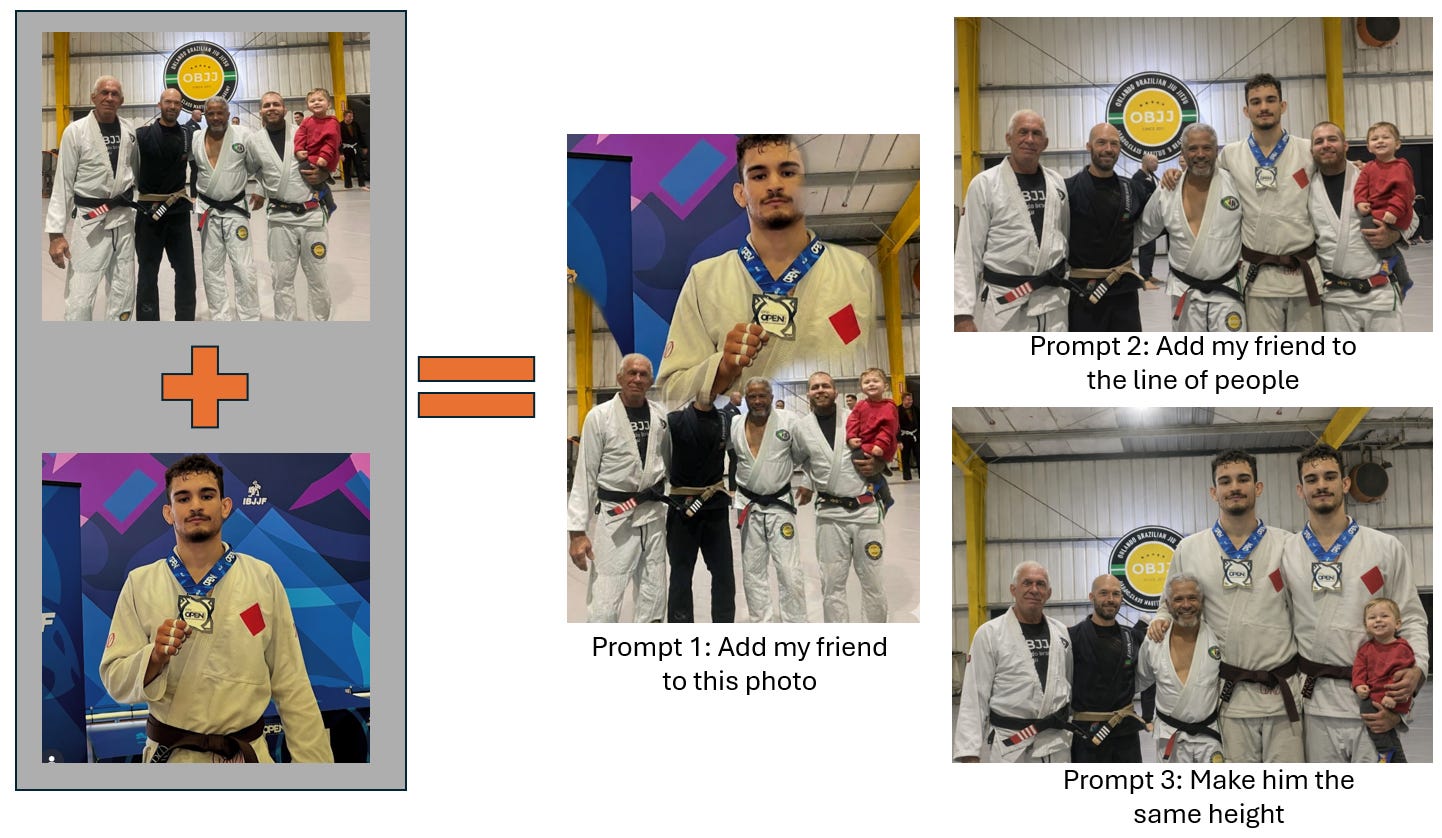

I use ChatGPT and Gemini every day. I’m writing this article because it’s some of the silly queries that expose the biggest cracks in how LLMs function. One of my friends was out of town this week so I asked Gemini Nano Banana Pro to add him to a group photo. This would take a human graphic designer maybe 30 minutes to make a B+ quality photo with scaled sizes, consistent lighting, color contrasts, and so on.

My first prompt was “add my friend to this photo” and the LLM followed the direction without understanding the context. While a human graphic designer wouldn’t make this mistake, my one sentence prompt wasn’t enough for a LLM.

I added more specificity to my second prompt with “add my friend to the line of people and don’t change any faces or features”. The new image generated by the LLM got the group photo concept right but got the scaling wrong as it him 7 feet tall while also changing everyone’s faces.

For the third prompt, I said “make everyone the same height and don’t change the faces”. The model made two 10-foot versions of him that are equal height, deleted one person (still leaving an extra hand), and made the three people on the left the same height with different faces.

How did AI get this simple task so wrong and why did each additional prompt make it worse? Four different critical errors happened:

“Salience latch” is an early-commitment error when the start of the chain of reasoning picks the wrong anchor subject.

“Same height” triggered scaling instead of placement logic.

Faces kept changing because the model regenerated an entirely new image instead of combining elements from the existing photos into a composite.

With multiple people in the picture, the model picked the lowest compute option by maintaining style + pose + context rather than preserving the complex faces. One guy vanished entirely because the model reallocated the ‘visual budget’ to process less data.

With a photo that I’m editing for fun, the only harm the LLM caused was wasting my time and tokens. These simple logic mistakes have huge consequences when AI is operating cars or issuing refunds as an autonomous customer service agent.

Real world impact (literally into a concrete wall)

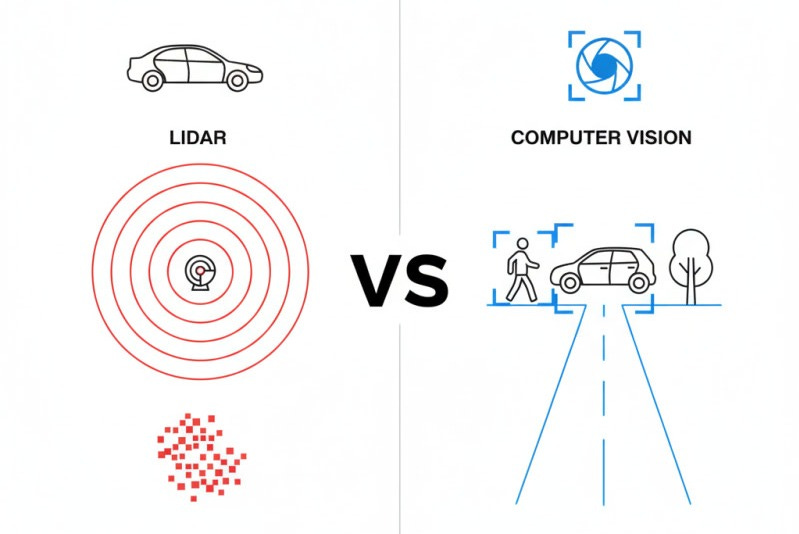

Tesla self-driving uses only computer vision with cameras to avoid the cost of spatial sensors like LiDAR that give actual proximity data. In the graphic below, LiDAR collects data points on the distance of every physical object around the vehicle while computer vision uses the cameras to make probabilistic classifications (person, car, tree) and approximates distances based on size. When Gemini got confused and made my human friend 10 feet tall (which a smart model with logic rules should know is impossible), you can see how computer vision driving a car can go very wrong.

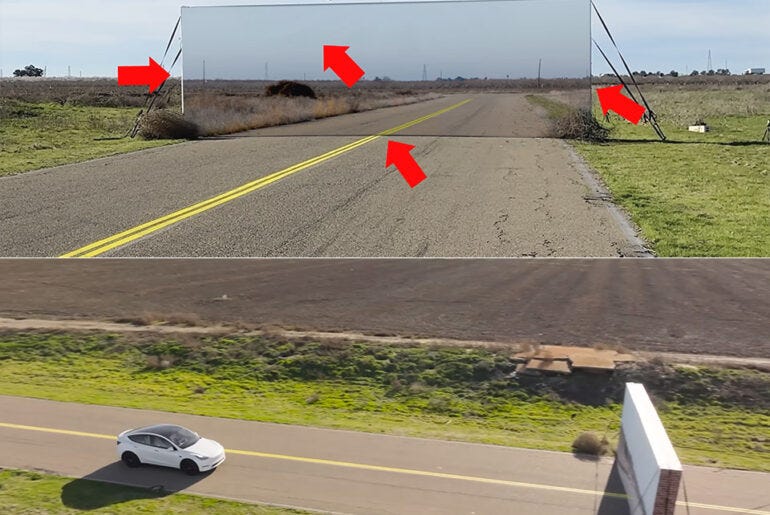

Tesla has killed at least 772 drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists for the same reasons my photo editing failed. Self-driving fails catastrophically when there is early latch → path dependence → compounding error.

If the Tesla decides to make a large moving object the primary hazard (or early latch just like my friend who was turned into a giant), then a stroller, wheelchair, or bike becomes secondary background noise. When construction messes with the normal lane patterns on a highway and the model decides that driving in the lanes is the highest priority (early latch), the model can be anchored on finding dashed lines above anything else when it drives at 80mph into a concrete barrier. I personally witnessed the fireball when a Tesla made that same fatal mistake on 101.

This isn’t a bug in the LLMs, it’s at the center of how they operate. The 2017 Google research paper, Attention Is All You Need, introduced the Transformer model architecture (ChatGPT = generative pre-trained transformer). By using self-attention alone to sequence relationships more efficiently and accurately, attention mechanisms let models decide what to focus on by assigning higher weight to certain inputs. But that focus is inherently probabilistic and context-dependent, not a guarantee of correctness.

Once attention locks onto a salient token, object, or feature early, downstream reasoning is conditioned on that choice which makes errors self-reinforcing rather than self-correcting. That’s why Gemini made my friend into a giant and then made two versions of him even bigger. Picking the wrong salient feature broke the entire chain of reasoning.

If Tesla’s salient object becomes finding and staying inside the lane markers, the car will drive directly into a concrete barrier because avoiding the barrier is less important than staying in the lane.

When you combine a LLM’s logic failures with cameras/computer vision that’s making probabilistic assumptions about object proximity (without real sensor data), a Tesla will drive into a wall that’s painted to look like a road.

The second fatal flaw in using computer vision with cameras instead of sensors is the model needs to estimate the size and position of objects. Just like Gemini turned my friend into a 10-foot-tall giant, a Tesla can misinterpret the scale of another vehicle and then make the wrong decisions based on a flawed size assumption.

Many of the fatal Tesla crashes involve the self-driving car ramming into the back corner of a tractor trailer. This can happen because the computer vision either estimates the truck is further away, the truck is smaller than it actually is (so the Tesla thinks it has room to pass), or the Tesla interprets the space under the truck as a clear path. Without sensors that measure actual distances, a breakdown in the logic chain is a constant risk with deadly consequences.

Tesla’s crashing problems are a deliberate decision they made to go cheap by using only cameras. A Waymo self-driving taxi has never been involved in a serious crash or fatality because it has 4 LiDARs, 6 radars, and 9 cameras that create a 4D map of the space around it. The cost of safety is very real. Estimates are the Waymo has about $60,000 in sensors while Tesla’s cameras are less than $1,000.

If you skip the sensor data in a self-driving car and depend on AI to interpret images, the biggest danger of AI operating in the real world isn’t hallucinations. Things go very wrong when an AI commits early to the wrong line of reasoning (like staying in the lane instead of avoiding barriers) and then executes a bad decision flawlessly.

Will AI Get Better?

Humans use natural intuition, double-check info, or ask clarifying questions when they are uncertain about key information. Inversely, LLMs treat uncertainty as a problem to be minimized or eliminated at the start of the logic chain. This difference explains why a human graphic designer wouldn’t make a person 10 feet tall, but a LLM will.

A lot of AI discourse is focused on “better prompting” to solve failures. But more prompts can have the opposite effect when an attention error creates a feedback loop with no way to reconcile mutually competing objectives (identity preservation, spatial realism, height constraints). Unlike a rules-based computer program, prompting is basically a negotiation with a probabilistic engine.

We need to realize that models aren’t minimizing errors because their priority is minimizing loss under compute constraints. Deleting a person, duplicating another, or regenerating faces isn’t a glitch, the LLM is making a rational resource tradeoff inside the system. Tech leaders keep saying “more data = better models” but more data also results in models focusing on the wrong or insignificant parts of the data.

As both my goofy pictures show, LLMs don’t fail because they hallucinate or lack adequate input data. They fail because they decide the wrong thing matters, and then they never recover from the doom loop of bad decisions.

David Riedman, PhD is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my podcast—Riedman Report: Risk, AI, Education & Security—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio and the New England Journal of Medicine.